It has nothing to do with consensus.

I have seen video of scientific conferences before. I would say, without looking at video links you've provided that it might matter (greatly) what field of science is the topic for the conference. To me, the consensus part comes before, in that all participants are hopefully going to have fundamental agreement on certain (set of) beliefs. As the whole body of science is so huge, I'm not sure our discussion (or really any amount of discussion) is going to address what I'm getting at, without it being considered too broad and not precisely true in a particular branch of science. As I noted before, when it comes to public health and particularly the science as it relates to smoking/vaping (health), I feel able to follow along with the science. The conferences that I've seen have agendas that are visibly set up to reinforce an agenda. How do I know this, because I am aware of who gets invited and who asked to attend and was denied. That's not as lopsided as one may infer from what I'm stating, but it is lopsided or not providing a visibly balanced approach. In the conferences I've seen the minority view was seemingly ignored at the conference, or not visibly debated during the conference. I've seen a few instances from actual practitioners where they spoke to what occurred afterwards, and at least one case where the majority position had its eyes opened via post conference dialogue, enough to blog about it (in extensive detail) to consider the other side, which appeared to me, a lot like moving away from the majority view, or consensus. I don't think I have ever seen a video of a conference, on this particular branch of scientific research, where participants engaged in the debate during the conference. I think it could happen, so am not saying it can't or won't. But am saying that given the consensus approach / majority position, and the way politics works to influence scientific understandings and research, I see it as a game being played to just say "we had a conference on this." And then manipulation of that to later say, "the minority position was presented, but the majority view was..." thus and so, or really what was already set up by the agenda to be how the conference would go.

Which makes scientific conferences, at least in the field I'm alluding to, show up as entirely superficial, and highly political.

So, I strongly disagree with the "it has nothing to do with consensus" assertion and welcome further debate on that.

I didn't mention pseudoscience, nor do I understand how anything I said involves pseudoscience in anyway. Texts and conferences aren't "pseudoscience" but a primary means of disseminating scientific knowledge.

Pseudoscience, as my computer's dictionary defines it: a collection of beliefs or practices mistakenly regarded as being based on scientific method.

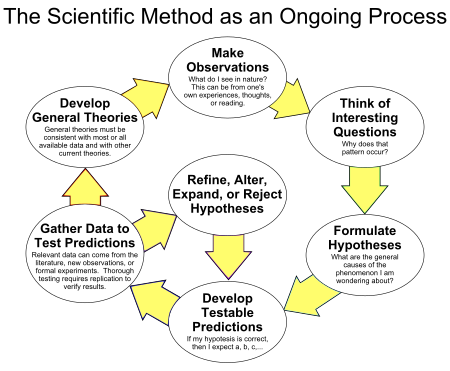

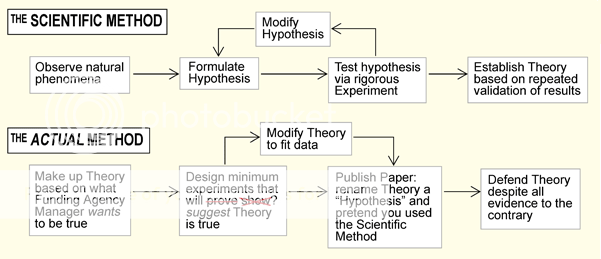

Given how this thread has transpired thus far, I don't see how one can not see how pseudoscience would not enter the picture. Either the scientific method is a consistent guideline that is mostly being followed by people that practice science, and that is well known, or there is a disconnect between the alleged method and actual scientific practice. Such that the actual collection of beliefs and practices are based on something other than the (mythical) scientific method.

Of the field I am aware of, it (pseudoscience) doesn't come up from the majority view. Perhaps occasionally, but I observe it rarely or never. But it comes up often from the minority position. Because those scientists know that the majority's view is based not so much on research, but a political game being waged. Seriously, anyone that is a proponent of science, go study the research as it stands right now for vaping. I welcome that. Come back here and report the findings, and I'll be quite interested in what you find, as it'll show me how much you dug around or did you just go with the consensus view, which is clearly based on pseudoscientific assertions that are currently held in place by 'consensus.' As I've done a lot of research on this, I now realize the same is true for smoking. Much more challenging debate to have there given how strong the consensus is, but because I know I'm not alone in my views and because of how familiar I am with the material, I welcome that debate. Instead, consensus view has seemingly no interest in further discussion, seeing the debate as settled. I see the majority view as willing to accept a lie (or 10) for great political gain, or endless amounts of funding.

What's not really science?

To me, it is about both. And in the reality of science as I see it, it will likely be about both for a long time to come. The philosophical aspect of science interests me more because, well it is cutting to the chase really. The political aspect is asking any person who cares about this discussion to get up to speed with all (or some) of the particulars in a branch of science, understand the key theories, what is currently being researched, the tools that are used, so on and so forth. Having understanding of the minority position(s) in the political arena, I find helpful if not necessary. But also is not the position that a philosophical inquirer or detractor would approach the current debate(s). That would likely be dismissed as impractical to the current debate(s), as you are attempting to do here.

If someone on RF posts a thread (in General Debates) that talks about how Abrahamic God is being misrepresented in most accounts that the layperson is given or accesses, I would think it plausible that in the course of that debate the proponents for religious belief would be sticking to the particulars that OP of that thread was aiming for. While atheists might (rightfully) enter that debate and suggest that there is a philosophical debate, which they are most interested in, that is seemingly being ignored. Perhaps the thread is allowed to handle both discussions. Perhaps both discussions relate, or perhaps some looking on decide the two are in no way connected, and the philosophical is off topic from what OP was intending. But, I still think if OP of that thread is claiming that the teachers of the subject are misleading the students with what actually is practiced later in life with regards to the topic (i.e. career in studying God), that an atheist might think that is highly relevant to the points they wish to discuss.

So, you ask what's not really science. And I tell you that the majority of scientific research around vaping (politics) is not really science. It is pseudoscience. And it is the majority view. It is visibly using political propaganda to gain more research and also using funds to forever downplay/ignore the minority view, which is partially to mostly the minority view because it is not granted unlimited funds by a government that benefits from perpetuating the lies associated with the majority view. That's a very specific example I give, that I believe pertains to this thread. Has, on the surface, little to do with the philosophical debate about science (and scientific method) in general. But has a lot to do with how science as an endeavor, that uses a top-down approach toward indoctrinating people into the field, does operate. Does mislead. Divergence from the current practice is discouraged. So much that if one is not aligned with the current, popular practices, they can plan on finding funding for their research elsewhere, and the popular, consensus based approach (based on pseudoscience) will rest quite comfortably knowing that the laypeople will look to them for 'knowledge' on what current science is understanding about a particular field.

Most scientific research would be inaccessible to you because it would require a level of mathematical competency you do not have. In some fields, you could learn the technical aspects of the field without needing to know at the very least multivariate statistics and some calculus, but you would still need to learn the technical aspects in order to read the research.

If it is strictly mathematical data, then I see it as ceasing to be science. Sorry if that disagrees with world paradigm, but I'm comfortable debating that further.

Also, if you don't have access to databases like ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, Nature Journals Online, Wiley Online Library, Academic Search Complete, IEEE, Proquest, JSTOR, etc., it can be quite difficult to even access the necessary literature, let alone possess the necessary familiarity with the subject matter to understand it.

I'm well aware of this. All of which ought to tell laypeople that this type of research doesn't actually apply to them, not meant for them. To the degree it is argued it does apply and ought to be considered by laypeople for (political) decisions going forward, then I'm sure access is granted in some fashion (via articles written by scientific types), all of which fit in with the misleading aspect that is what this thread is getting at.

So, science in want to have it both ways? And finding it challenging now that you've set it up with special privileges for the elite to have direct access and the layperson to never have access. I hope that works out for you. Observably, in this thread, it is problematic, and is noticeably misleading the laypeople into what scientific practice actually entails.

Science works just fine. It just doesn't work according to the mythical The Scientific Method idealization of 18th &19th century experiments in physics and chemistry that underlies to popular model of scientific inquiry in pre-college/early undergraduate education AND popular literature.

Science works fine in the way religion works fine, or anything works fine from its proponents' view. It's working quite well (read as successful business model) for practitioners who fall in line and who don't deviate too far from the consensus. Not so fine for those who branch out from this and stay within the domain of science, but are out of touch with the majority view. And inaccessible to laypeople who aren't granted open access to research for peer review, or shared understanding.

Like all things on the planet today, science is scrutinized at many levels. It is mocked, disregarded at times, and not seen as all that much better of an approach to any other endeavor (i.e. philosophy, religion/spirituality, art, etc.). It's proponents will disagree, but let's see how well they fare in open debate. I can't wait.