It seems each translation has certain things that they get right and lots of things that they get either wrong or purposely colored Theologically (i.e. blatantly changed to support doctrine).

For example, the KJV and Douay Rheims gets Mark 7:19 correct, in saying that the Stomach purges all foods, while most modern translations deliberately distort the present tense into the past and twist the grammar to make it say that Jesus changed the dietary restrictions.

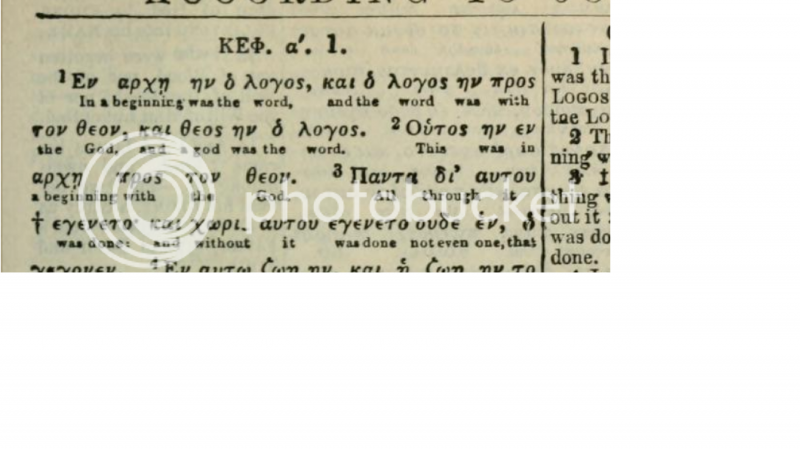

The NWT and other minority Scholarly works accurately reflect that John 1:1c should read "And the word was a god" as well as John 10:33 "You make yourself a god", while some like Goodspeed's "An American translation" get the right gist by translating Theos as "Divine", whereas most other translations use "Word was God" purely out of Theological reasons, with invented (and even disputed by other Trinitarians) "rules" like Colwell's to reinforce their traditional rendering.

In many cases though, even the JPS may get things a bit distorted as it's sometimes based more so on KJV rendering, and that's not even touching on the issue of Masoretic text issues.

Sometimes only a single lone translation gets the nuances of the language, such as the Good News Bible accurately translating "Do not take revenge" instead of the most commonly botched "Do not resist an evildoer" that every other translation seems to have. (I will be happy to explain in detail why the Good News version alone gets Matthew 5:39 right but it might be best for a whole thread).

39 But now I tell you: do not take revenge on someone who wrongs you.

In some cases such as Zechariah 12:10 it's hard to find a single translation that gets it right, judging by how the NT authors read it. In John 9, Jesus quotes it as "him who they pierced", as the pronoun indicator is a bit vague, but the other translations seem to have no problem rendering it as "Me who they have pierced", so Jesus or John must have had either a different version, or its an example of where Theological coloring gives way to blatant inconsistencies, and in cases like this, even the JPS and Jewish translations aren't necessarily better since its a case where the Hebrew, let alone Masoretic rendering is unclear and up to interpretation.

Sometimes like in Psalm 8:5, the translators refuse to accept the idea of Heavenly beings called "gods" and have odd renderings like "Man was made a little lower than God", and then have no problem that Hebrews quotes the verse as "Man was made a little lower than the Angels". In many cases, it seems consistency is not even of concern when it comes to their Theological coloring and fear of ruffling feathers of their audience who arent' familiar with the nuances of the old Israelite culture.

And in some cases, the NLT gets the gist of passages correct where others don't, (and in many cases fails miserably). And manuscript and text-interpolation issues aren't even an issue on this yet.

In some cases the JPS however gets somethings more right that none of the "Christian" leaning translations get, like Psalm 45:6, where it's commonly (and incorrectly) rendered as "Thy throne, O god" when it should be more along the lines of "God is thy throne". Sometimes I wonder if that verse is deliberately distorted, which is clearly talking about a King and not God, for the sake of a Trinitarian rendering of its quote in Hebrews 1:8. Which leads me to the next subject:

An issue I rarely see discussed is that HEBREW HAS NO VOCATIVE. When I see that 'O" before God or whatever, it is definitely annoying. I suppose it helps the reader identify the subject being talked to, but a comma works just as well and doesn't sound as pretensious. "O this, O that".