Ok. I got a hold of the first study in the article.

BBC said:

UK scientists, writing in Science, looked at how brain size varied depending on how much people thought about decisions.

But a nationwide survey recently found that some people think too much about life.

These people have poorer memories, and they may also be depressed.

As I stated earlier, the Journalist has combined two unrelated studies. This beginning introduction is true, but the first sentence which I've highlighted, has nothing to do with the second. Combined, it deceptively appears as though brain size has been linked with poor memory and depression.

BBC said:

Stephen Fleming, a member of the University College London (UCL) team that carried out the research, said: "Imagine you're on a game show such as 'Who Wants to Be a Millionaire' and you're uncertain of your answer. You can use that knowledge to ask the audience, ask for help."

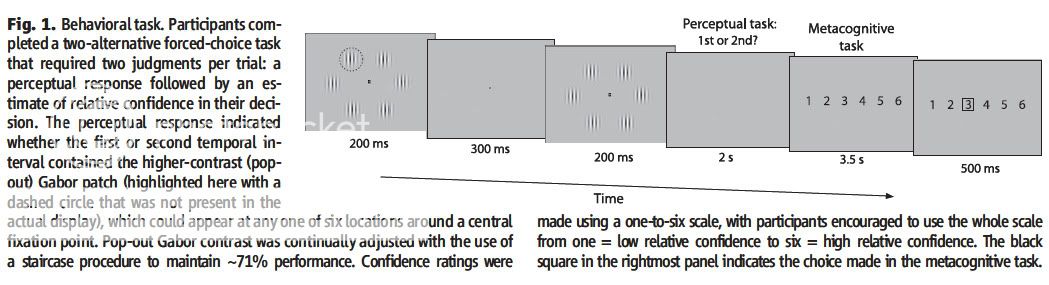

The London group asked 32 volunteers to make difficult decisions. They had to look at two very similar black and grey pictures and say which one had a lighter spot.They then had to say just how sure they were of their answer, on a scale of one to six.

I believe this is inaccurate. The perceptual task involves the flashing of two screens, which lasts for 200 ms each with a 300 ms blank pause in between. The subjects see two striated blips while staring at the screen, and then decide which screen had the higher contrast blip. This is not a difficult task at all, and that is not really what this study is about. This study has

absolutely nothing to do with "too much thought." It has to do with metacognitive ability in determining the accuracy of our decisions. This was measured by a scale of 1-6 in the metacognitive task, in which the subject rated how confident he/she was in his or her decision. This variable was correlated with anatomical volume of grey and white matter. A significant positive correlation between subject confidence and brain volume in the PFC was found.

BBC said:

People who were more sure of their answer had more brain cells in the front-most part of the brain - known as the anterior prefrontal cortex.

This part of the brain has been linked to many brain and mental disorders, including autism. Previous studies have looked at how this area functions while people make real time decisions, but not at differences between individuals.

Both of these statements are true. However, the journalist has again combined two unrelated things, which deceptively gives the appearance that more brain cells in the anterior PFC equates to brain and mental pathology. If anything, the researchers in the first study linked brain lesions in the PFC with a compromised metacognitive ability:

original study said:

Consistent with prefrontal gray-matter volume playing a causal role in metacognition, patients with lesions to the anterior PFC show deficits in subjective reports as compared with controls, after factoring out differences in objective performance

BBC said:

The study is the first to show that there are physical differences between people with regard to how big this area is. These size differences relate to how much they think about their own decisions.

True, as I stated, a pretty considerable correlation was found.

BBC said:

The researchers hope that learning more about these types of differences between people may help those with mental illness.

This may be true, but in the context that people who have lesions in their PFC are suffering from neurological deficits, not the other way around.

BBC said:

Co-author Dr Rimona Weil, from UCL's Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, said: "I think it has very important implications for patients with mental ill health who perhaps don't have as much insight into their own disease." She added that they hope they may be able to improve patients' ability to recognise that they have an illness and to remember to take their medication.

However, thinking a lot about your own thoughts may not be all good.

Again, there is a combining of two unrelated studies. In the first study, it is likely that Dr. Rimona is referring to people who are suffering from a metacognitive deficit due to a lesion, tumor, or something else. It is possible that thinking a lot about your own thoughts may not be all that good, but this premise has nothing at all to do with the first study.

Metacognition, for example, is the realization that the memory of what you ate for last nights dinner may not be accurate. It is being aware of your own thought and memory processes. To suggest that being aware of your own thoughts and cognitive processes may not be all that good, is absurd [edit: not necessarily]. A Metacognitive deficit in memory for example, would lead to an inability to tell whether or not your memory of an event is vivid and accurate, or that perhaps your memory is not a memory at all--perhaps you dreamed it and only mistook it for a memory. When we say things such as, "I'm sorry, what's your name again? I'm very bad at memorizing names," we refer to our memory and how bad it is. This realization, of how good or bad our memory is, is metacognition. People who suffer from Alzheimers, exhibit metacognitive deficits (as well as memory deficits), which is who Dr. Rimona might actually be referring to, as they also exhibit

anosognosia, a lack of awareness that they are suffering from a condition.

BBC said:

Cognitive psychologist Dr Tracy Alloway from the University of Stirling, who was not involved in the latest study, said that some people have a tendency to brood too much and this leads to a risk of depression. More than 1,000 people took part in a nationwide study linking one type of memory - called "working memory" - to mental health. Working memory involves the ability to remember pieces of information for a short time, but also while you are remembering them, to do something with them.

For example, you might have to keep hold of information about where you saw shapes and colours - and also answer questions on what they looked like. Dr Alloway commented: "I like to describe it as your brain's Post-It note." Those with poorer working memory, the 10-15% of people who could only remember about two things, were more likely to mull over things and brood too much. Both groups presented their findings at the British Science Festival, held this year at the University of Aston in Birmingham.

The Journalist failed to cite or place a link for this study. Various things in this section of the article is true, and is most likely referring to the well known phenomenon called rumination. Rumination and metacognition or introspective ability are not the same thing [edit: though they may be inter-related. For example, rumination may involve metacognitive processing]. Working memory and metacognition are also not the same thing.

[edit: after doing some more research on metacognition and rumination I have changed my mind concerning the article. There are studies that have linked the two (click here for an example). This leads me to drop the assertion that the article was deliberate convolution. Instead, I believe it to be neglect on the journalist's part to write a more well thought out and scientifically accurate article. It appears that the journalist was trying to link metacognition with rumination and depression (but did so poorly). If anyone is interested in this subject matter, I suggest using these three terms when performing a search].