First, thanks for such an excellent series of posts.I've been reading about Gobekli Tepe - a 12,000 year old cult complex, the oldest example of monolithic architecture yet discovered - for a number of years now. It should be far more well known since it is a game-changing site for understanding the origins of civilization. Read from the archaeologist's blog:

The Tepe Telegrams

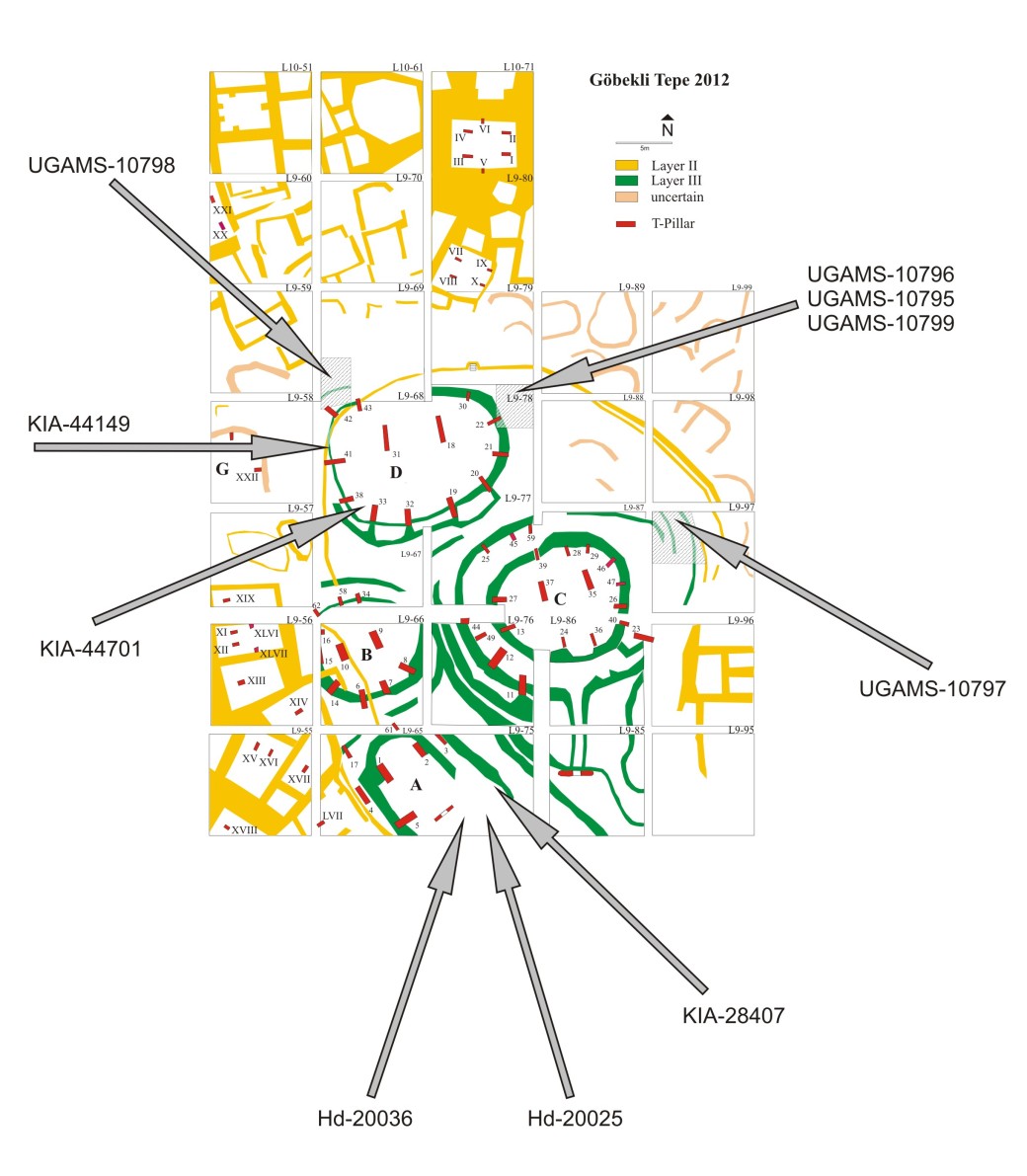

A few kilometres northeast of modern Şanlıurfa in south-eastern Turkey, the tell of Göbekli Tepe is situated on the highest point of the otherwise barren Germuş mountain range. Rising 15 metres and with an area of about 9 hectares, the completely man-made mound covers the earliest known monumental cult architecture in the ancient Near East. Constructed by hunter-gatherers right after the end of the last Ice Age, they also intentionally buried it about 10,000 years ago.Traditional thought went something like this:

No typical domestic structures have yet been found, leading to the interpretation of Göbekli Tepe as a ritual centre for gathering and feasting. The people creating these megalithic monuments were still highly mobile hunter-foragers and the site’s material culture corroborates this.

In the centre two colossal pillars, measuring about 5.5 m, are founded in shallow pedestals carved out of the carefully smoothed bedrock. This central pair of pillars is surrounded by a circle formed of similar, but slightly smaller pillars which are connected by stone walls and benches.

Hunter gatherers---> farming ------> Settlements, civilization, organised religion (made possible from farming surplus)

But at Göbekli Tepe it seems to have gone:

Hunter Gatherers-----> organised religion/cult/spiritual beliefs -----> farming, full settled life and civilization

....with the religion bringing more people together on a more permanent basis in one place, such that they needed farming to feed them and indicates a significant shift in worldview from the earlier “cave art” beliefs. In these, Paleolithic people appear to have seen themselves as simply “part” of their natural world, on a similar level to the animals depicted – I suppose a sort of “animistic” religious outlook, if it isn’t anachronistic to say that.

But with Gobekli Tepe, stylized human figures take centre stage for veneration and ritual focus, towering above the animals that lie beneath and the surrounding landscape. This suggests a shift to a more “anthropocentric” worldview in which humans are believed to be ‘above’ the rest of nature and perhaps able to exert a kind of ‘mastery’ over the wild forces of nature represented by the fearsome beasts, which apparently gave these ancient Neolithic people the impetus to start experimenting for the first time in human history with agriculture.

It used to be taken for granted by anthropologists in the early 20th century that climactic change at the end of the last Ice Age (the Younger Dryas) led to the invention of agriculture and spurred humans to abandon hunter-gatherer society and embrace full sedentary living, which enabled settlements, civilisation, art and religion to ultimately develop. There were already problems with this theory before GT was discovered in the 1990s, not least that earlier warming periods in human history had not resulted in any great quantum leap for our species out of the Stone Age, indicating that more was at play here.

Gobekli Tepe pivots this assumption on its head.

According to Gobekli, it was the urge to worship and exchange knowledge that originally brought human beings together to construct elaborate monolithic structures for ritual use before the invention of agriculture or fully settled life as we know it. Basically, the process of constructing the cultic site of Gobekli made it necessary to find a more consistent found source which probably led to the first domestication of wheat to feed those working on the construction.

Those researching and excavating the site are of the opinion that it had a cultic, ritual use rooted in the belief system of hunter-gatherers. They aren't saying this without good reason.

We have no idea if these people had any conception of gods but the architecture in question had a cultic significance for the people who built it and was constructed for ritualized feasting etc. rooted in a belief system/shared religious understanding. If I might quote the researchers again:

https://www.researchgate.net/public...of_Upper_Mesopotamia_A_View_from_Gobekli_Tepe

"...Vast evidence for feasting at the site seems to hint at work feasts to accomplish the common, religiously motivated task of constructing these enclosures. Given the significant amount of time, labor, and skilled craftsmanship invested, and as elements of Göbekli Tepe’s material culture can be found around it in a radius of roughly 200 km all over Upper Mesopotamia , it is likely that the site was the cultic center of transegalitarian groups..."

And again:

https://tepetelegrams.wordpress.com

"...While these surrounding pillars often are decorated with depictions of animals like foxes, aurochs, birds, snakes, and spiders, the central pair in particular illustrates the anthropomorphic character of the T-pillars. They clearly display arms depicted in relief on the pillars’ shafts, with hands brought together above the abdomen, pointing to the middle of the waist. Belts and loincloths underline this impression and emphasize the human-like appearance of these pillars.

Their larger-than-life and highly abstracted representation is intentionally chosen and not owed to deficient craftsmanship, as other finds like the much more naturalistic animal and human sculptures clearly demonstrate. This suggests that whatever the larger-than-life T-pillars are meant to depict and embody is on a different level than the life-sized sculptures in the iconography of Göbekli Tepe and the Neolithic in Upper Mesopotamia.

Furthermore, these objects are not restricted to Göbekli Tepe and the few other sites with T-shaped pillars in its closer vicinity, but are known from places up to 200 km around the site. A spiritual concept seems to have linked these sites to each other, suggesting a larger cultic community among PPN mobile groups in Upper Mesopotamia, tied in a network of communication and exchange.

In this scenario, the early appearance of monumental religious architecture motivating work feasts to draw as many hands as possible for the execution of complex, collective tasks is changing our understanding of one of the key moments in human history: the emergence of agriculture and animal husbandry – and the onset of food production and the Neolithic way of live..."

(Continued....)

The one thing I would say is that when one compares the religions of hunter gatherers (American Indians, San people, Australian aboriginals) one sees that their religion and mythology is no less rich and vivacious as compared with sedentary farming cultures. So if one is going to say that religious beliefs created the conditions that led to farming revolution etc. one would have to point to what is unique among the religions of those cultures that developed farming as opposed to those people who never developed farming or settled lifestyle. And one has to tie that unique feature with the incentive to settle and farm.

I believe what Gobleki Tepi shows is that this region was exceptionally ecologically rich, so that hunter gatherers could generate enough surplus to develop extensive and elaborate material culture including large scale elaboration of their cultic beliefs through cult centers and religious architecture. This very same ecological richness made it possible for these groups to develop settlements without developing farming. And this settling in created the conditions that spurred domestication of crops and eventually livestock.