Rakovsky

Active Member

Egypt's civilization is considered to have begun about 5000 BC, and its writing is dated to have begun in 3500-3100 BC. The First Egyptian Dynasty dates from 3100 BC.

Scholars debate the extent of monotheism in ancient Egypt, and those who find monotheism in their religion may point to the following:

A famous Egyptologist of the early 20th century, EA Budge, found the word God (NTR) written by itself numerous times without reference to a specific deity of the Egyptian pantheon, and he concluded that this showed a belief in a one true God:

Budge writes in TUTANKHAMEN: AMENISM, ATENISM AND EGYPTIAN MONOTHEISM:

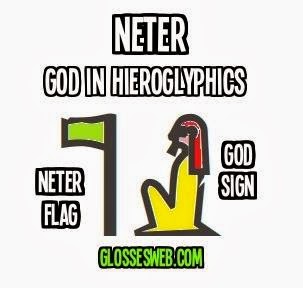

Budge then cites the Precepts of Kagemna (IVth dynasty) and the Precepts of Ptah-hetep (Vth dynasty):But in the Collections of Moral Aphorisms, or "Teachings," composed by ancient sages, we find several allusions to a divine power to which no personal name is given. The word used to indicate this power is NETER or NETHER. Many have tried to assign a meaning to this word and to find its etymology, but the original meaning of it is at present unknown. The contexts of the passages in which it occurs suggest that it means something like "eternal God." The same word is often used to describe an object, animate or inanimate, which possesses some unusually remarkable power or quality, and in the plural neteru, it represents the beings and things to which adoration in one form or another is paid. The great God referred to in the Moral Aphorisms is also spoken of as pa neter, "the God,"

1. The things which God, (neter), doeth cannot be known.

2. Terrify not men. God, (neter), is opposed thereto.

3. The daily bread is under the dispensation of God, (neter).

4. When thou ploughest, labour (?) in the field God, (neter), hath given thee.

5. If thou wouldst be a perfect man make thy son pleasing to God, (neter).

6. God, I 1, loveth obedience; disobedience I is hateful to God, (neter).

7. Verily a good (or, beautiful) son is the gift of God, (neter).

You can read Budge's chapter here:

http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/tut/tut12.htm

He cites hymns and poems to God. For example, he cites the Teaching of Amenemapt, the son of Kanekht, c. XVIIIth dynasty:

1. Leave the angry man in the hands of God . . . God knows how to requite him (Col. V).

2. Carry not away the servant of the God for the benefit of another (Col. VI).

3. Take good heed to Nebertcher, (Lord of the Universe) (Col. VIII).

4. Though a man's tongue steers the boat, it is Nebertcher who is the pilot (Col. XIX).

5. Truth is the great porter (or bearer) of God (Col. XXI).

6. Seat thyself in the hands of God (Col. XXII).

7. A man prepares the straw for his building, but God is his architect.

It is he who throws down, it is he who builds up daily.

It is he who makes a man to arrive in Amentt (the Other World) [where] he is safe in the hand of God (Col. XXIV).

8. The love of God, praised and adored be he is more than the respect of the Chief (Col. XXVI).

Budge notes that in Chapter CXXV of the Egyptian Book of the Dead,

the deceased says in his declaration before the Forty-two gods, "I have not cursed God," and "I have not contemned the god of my city 1. The distinction between "God" and "god of the city" was quite clear in the mind of the Egyptian. The passages from the Moral Papyri quoted above show that the Egyptian priests and learned men were monotheistic, even though they do not proclaim the oneness of the god to whom they refer.

Wikipedia's entry on "Ancient Egyptian Deities" notes:

Scholars have long debated whether traditional Egyptian religion ever asserted that the multiple gods were, on a deeper level, unified. Reasons for this debate include the practice of syncretism, which might suggest that all the separate gods could ultimately merge into one, and the tendency of Egyptian texts to credit a particular god with power that surpasses all other deities. Another point of contention is the appearance of the word "god" in wisdom literature, where the term does not refer to a specific deity or group of deities.[118] In the early 20th century, for instance, E. A. Wallis Budge believed that Egyptian commoners were polytheistic, but knowledge of the true monotheistic nature of the religion was reserved for the elite, who wrote the wisdom literature.[119] His contemporary James Henry Breasted thought Egyptian religion was instead pantheistic, with the power of the sun god present in all other gods, while Hermann Junker argued that Egyptian civilization had been originally monotheistic and became polytheistic in the course of its history.

The Canadian Anthropologist Arthur Custance argued that Egyptians were originally monotheistic in that each local Egyptian community worshiped one particular god and it was only later as Egyptian society and its cities united that it began to bring them into a pantheon with many gods. He noted:

Sir Flinders Petrie, in an excellent little book on the subject of Egyptian religion, wrote as follows:

- There are in ancient religions and theologies very different classes of gods. Some races, as the modern Hindu, revel in a profusion of gods and godlings which continually increase. Others . . . do not attempt to worship great gods, but deal with a host of animistic spirits, devils, or whatever we may call them. . . . But all our knowledge of the early positions and nature of the great gods shows them to stand on an entirely different footing to these varied spirits. Were the conception of a god only an evolution from such spirit worship we should find the worship of many gods preceding the worship of one god. . . . What we actually find is the contrary of this, monotheism is the first stage traceable in theology. . . . Wherever we can trace back polytheism to its earliest stages, we find that it results from combinations of monotheism. In Egypt even Osiris, Isis, and Horus, so familiar as a triad, are found at first as separate units in different places: Isis as a virgin goddess, and Horus as a self-existent God.

Several pharaohs acknowledged God in the Bible without equating Him with any specific pagan deity. For example, in Genesis 41, Joseph explained Pharaoh's dreams:

- 38 And Pharaoh said to his servants, “Can we find such a one as this, a man in whom is the Spirit of God?”

- 39 Then Pharaoh said to Joseph, “Inasmuch as God has shown you all this, there is no one as discerning and wise as you.

Joseph in the Bible

Some Egyptologists propose that the Egyptians used synchretization of gods to merge them into one God (eg. Amun + Ra = Amun-Ra), or that they saw many gods as being in reality emanations, aspects or portrayals of the one true God.

Wikipedia notes:

A god could be called the ba of another, or two or more deities could be joined into one god with a combined name and iconography... This linking of deities is called syncretism[, which] acknowledged the overlap between their roles, and extended the sphere of influence for each of them. Syncretic combinations were not permanent; a god who was involved in one combination continued to appear separately and to form new combinations with other deities.[114] But closely connected deities did sometimes merge. Horus absorbed several falcon gods from various regions...

...

Jan Assmann maintains that the notion of a single deity developed slowly through the New Kingdom, beginning with a focus on Amun-Ra as the all-important sun god.[124] In his view, Atenism was an extreme outgrowth of this trend. It equated the single deity with the sun and dismissed all other gods. Then, in the backlash against Atenism, priestly theologians described the universal god in a different way, one that coexisted with traditional polytheism. The one god was believed to transcend the world and all the other deities, while at the same time, the multiple gods were aspects of the one. According to Assmann, this one god was especially equated with Amun, the dominant god in the late New Kingdom, whereas for the rest of Egyptian history the universal deity could be identified with many other gods.[125] James P. Allen says that coexisting notions of one god and many gods would fit well with the "multiplicity of approaches" in Egyptian thought, as well as with the henotheistic practice of ordinary worshippers. He says that the Egyptians may have recognized the unity of the divine by "identifying their uniform notion of 'god' with a particular god, depending on the particular situation."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_deities

Professor Richard A Gabriel writes in Gods of Our Fathers: The Memory of Egypt in Judaism and Christianity,

The tendency toward monotheism in Egyptian religion was very old... found first in the Ptah and heliocentric texts of the Memphite Drama... The Egyptians understood that the local gods were very different from the major gods in the same way, perhaps, that Christian saints differ from the deity. The Egyptians arrived at the proposition early on that all gods were but different manifestations or permitted forms of the same one god. Thus the observance of the many gave rise to the belief in the One god and to the Egyptian idea that One is All... The same common elements of the one god first identified in the old texts reappear during the New Kingdom as the characteristics of Amun-Re. .. He is a god whose birth is secret, whose place of origin is unknown, whose birth is not witnessed, who created himself by himself, and who keeps his nature concealed from all who come after him. He is "the Hidden One." Yet He exists and is the source of all else...

The singularity of the trinity was reflected linguistically by the Egyptian use of the singular pronoun He when applied to god as trinity, in much the same way as the Christian God is referred to as He... The oldest known Egyptian trinity iis that of Ptah, Osiris, and Sokaris, the latter being the local god of Memphis. In an Egyptian trinity, like the Christian Trinity, the unity of the parts constitutes a genuine singularity, that is, one god. Each of the persons within the Egyptian and Christian trinity has an independent existence, is distinct in nature, is equally divine, and has its own powers even as, at the same time, each is part of the singular monotheistic unified god.

Ra-Horakhty, a synchretization of Ra and Horus