When you enter the land that God your Lord gives to you, and you shall possess it and dwell in it. Then you shall take from the first of all the fruits of the earth that you shall bring from the land that God your Lord gives you, and you shall place them in a basket. You shall go to the place that God will choose to cause His name to dwell there. You shall approach the Cohen who shall be there at that time, and shall say to him: "I declare this day before God your Lord that I have come into the land that God swore unto our ancestors to give us." The Cohen shall take the basket from your hands and place it down before the altar of God your Lord.

You shall proclaim before God your Lord: "ARAMI 'OVED AVI. He went down to Egypt and sojourned there few in number, and there became a great, powerful and populous nation. The Egyptians dealt harshly with us and afflicted us, and put upon us difficult labor. We cried out to God the Lord of our ancestors, and God heard our voice, saw our affliction, our burden, and our distress. God took us out of Egypt with a strong hand, an outstretched arm, awesome acts, signs and wonders. He brought us to this place, and gave us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey. And now I have brought the first fruits of the earth that you have given me God," and you shall put them down before God your Lord and prostrate yourself before God your Lord.

You shall rejoice in all the good that God your Lord has given to you and to your household, you and the Levite, and the convert that dwells in your midst (Devarim 26:1-11). - source

Meaning?

Rashi: 11th century

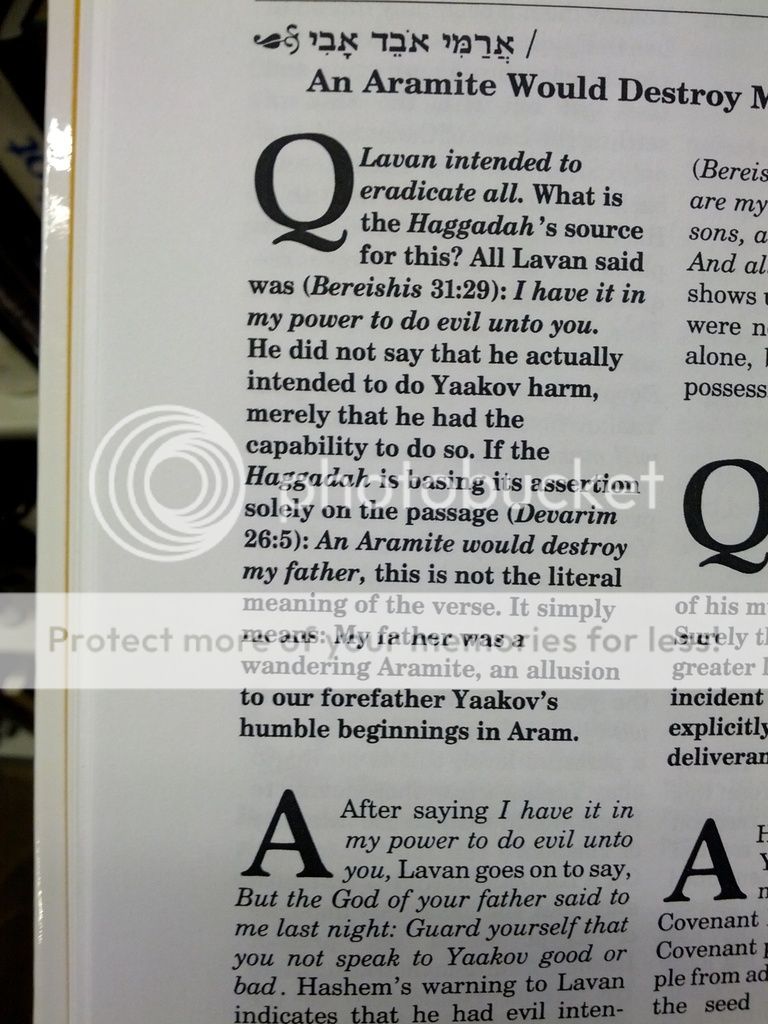

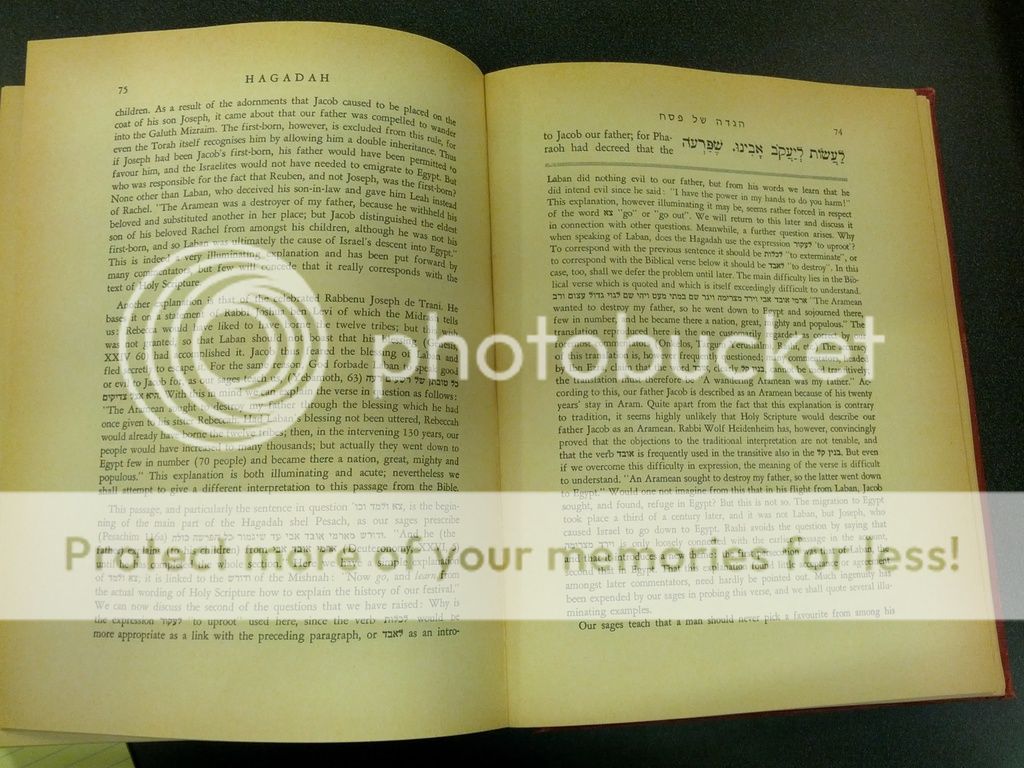

Arami oved Avi. (An Aramean sought to destroy my father). Laban sought to uproot all when he pursued after Jacob. And because he contemplated doing so, God charges him as though he had done it for as regards the nations of the world the Holy One Blessed Be God considers a thought equivalent to a deed.

Perhaps, but many modern translations are more in line with …

Rashbam: 12th century

Arami oved Avi. (My father was a wandering Aramean). My father Abraham was an Aramean, wandering and exiled in the land of Aram. As it is written, "Go forth from your land" (Genesis 12:1) and as it's written, "So when God made me wander from my father's house" (Genesis 20:13).

Ibn Ezra: 12th century

Arami Oved Avi. (a lost Aramean). The word "oved" is intransitive. And if the word "Arami" were to indicate Laban, the text would have written "ma'abed" or "ma'avid." And furthermore, what is the reason to say that Laban wanted to kill my father and went down to Egypt, and Laban never turned to go down to Egypt! The closer reading is that the Aramean was Jacob. As if the text said, when my father was in Aram he was enslaved, a poor person without money.

It seems to me that the central midrash in our Haggadah does a disservice by moving from

Once we were the Other ...

to

The Other tried to destroy us!

I'd love to see a Haggadah reclaim what to many seems to be the original meaning of the phrase.